Art and COVID while incarcerated: Guest essay

Corey Devon Arthur shares his experience making art during the pandemic.

Corey Devon Arthur shares his experience making art during the pandemic.

Corey Devon Arthur shares his experience making art during the pandemic while incarcerated

By Makeda Easter and Corey Devon Arthur

In late 2020, I wrote a story about an L.A. exhibition exploring the impact of COVID-19 on artists who have experienced incarceration. Over the course of my reporting, I spoke to several artists about their work, the show’s curator, and the founder of an organization that leads art workshops in California prisons.

While I had read about the devastation of COVID in prisons, I hadn’t considered what the pandemic meant for incarcerated artists and others who participated in arts programming, oftentimes one of the few sources of creative release. Working on the L.A. Times story made me want to dig even deeper into how incarcerated artists have coped during the pandemic.

How did they make art when they were banned from moving around freely, and even more confined to their cells? How were prison art programs affected? What impact did the pandemic have on the art itself?

Inspired by Scalawag Magazine’s Press in Prison guidebook, I wanted to amplify the voice of someone on the inside. For this newsletter, I’ll be sharing an essay from visual artist and writer Corey Devon Arthur.

I was connected to Arthur through Empowerment Avenue, a program that uplifts incarcerated artists and writers by pairing them with outlets and venues to share their work.

For much of the pandemic, Arthur was incarcerated at the Fishkill Correctional Facility in Beacon, New York. In January, he was transferred to Otisville Correctional Facility. He has written about his experience in outlets including The Marshall Project and The Drift.

Official arts programming at Fishkill is led by the nonprofit, Rehabilitation through the Arts, which operates in six men’s and women’s facilities across New York. Through hired teachers and volunteers on the outside, RTA offers classes in theater, dance, music, writing, and visual arts.

When the pandemic hit, RTA, like many other outside programs, could not enter prisons. They had to find creative ways to get inside, says Charles Moore, RTA’s director of operations.

And so the organization began sending self-guided lessons including scene study and in visual arts through snail mail, cassettes, and DVDs. They started filming material, so that a team of leaders on the inside could teach participants.

At one point, RTA sent in a sheet of paper simply asking, “how are you guys doing?”

“And that was the most successful thing we could have done, because they all started writing about how scared they were, how they were losing family members,” Moore says. “It was a real eye opener.”

Throughout the pandemic, RTA had starts and stops with in-person programming. Last June, the group went in again, but were locked out months later as Omicron surged in December. RTA eventually received permission to send lessons through JPay, a prison-based email service. And earlier this year, the group got approval to resume in-person.

(You can see some of the art made by RTA members on Facebook and Instagram.)

Arthur however, helped lead a small group of artists who work outside of any formal group, called the Fishkill General Library Illustration Group. He describes himself as a “bottom artist,” one without prestige.

“We're ragtag misfits with no home, and we don’t conform to institutional standards.”

Incarcerated artists have always had to find creative ways to make work. Arthur says he’s used everyday items like grape juice to tone paper, collard greens for making foliage, and shampoo, soap, or spit as a thickener.

The group’s pandemic-inspired art include social distancing signs and murals made using acrylic paint, watercolor, and markers. Arthur estimated his group created 75 original pieces, and copied about 1500 signs.

"The administration loved it because it helped them comply with COVID guidelines. The population thought it was cool. We also made coloring pages for kids when visits resumed.”

Learn more about his experience in the vivid essay he wrote earlier this year.

Bottomed Out

By Corey Devon Arthur

In March of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic painted over their pretty portraits with depression and death. It left the Fishkill Correctional Facility Rehabilitation Through The Arts (RTA) program comatose.

At the bottom we swerved differently. We drew in the dark. Despite the COVID complications within the Department of Corrections, we pushed our craft through the cracks. As the Inmate Liaison Committee Chairman and co- founder of the Fishkill General Library Illustration Group, I was the first one to bust my brush for the people.

The RTA folks kept it clean, which meant that they didn't have any dealings with us bottom artists. We drew with cigarette ashes and dirt from the yards if we had to. They were too well trained and bred to associate with the likes of us. Unlike us, they couldn't function without their outside volunteer civilians. COVID had denied all volunteers entry into the prison. They fell back and played the cut, while we oozed out of it like an infection.

Cheryl Bennin, the senior Librarian at Fishkill Correctional Facility was the bag lady. She made sure that we had what we needed to deliver the goods to the people. She gave me the supplies on consignment and said, "I don't care how you do it, just get it done and make it look good. Put it on for the people." That made me the plug.

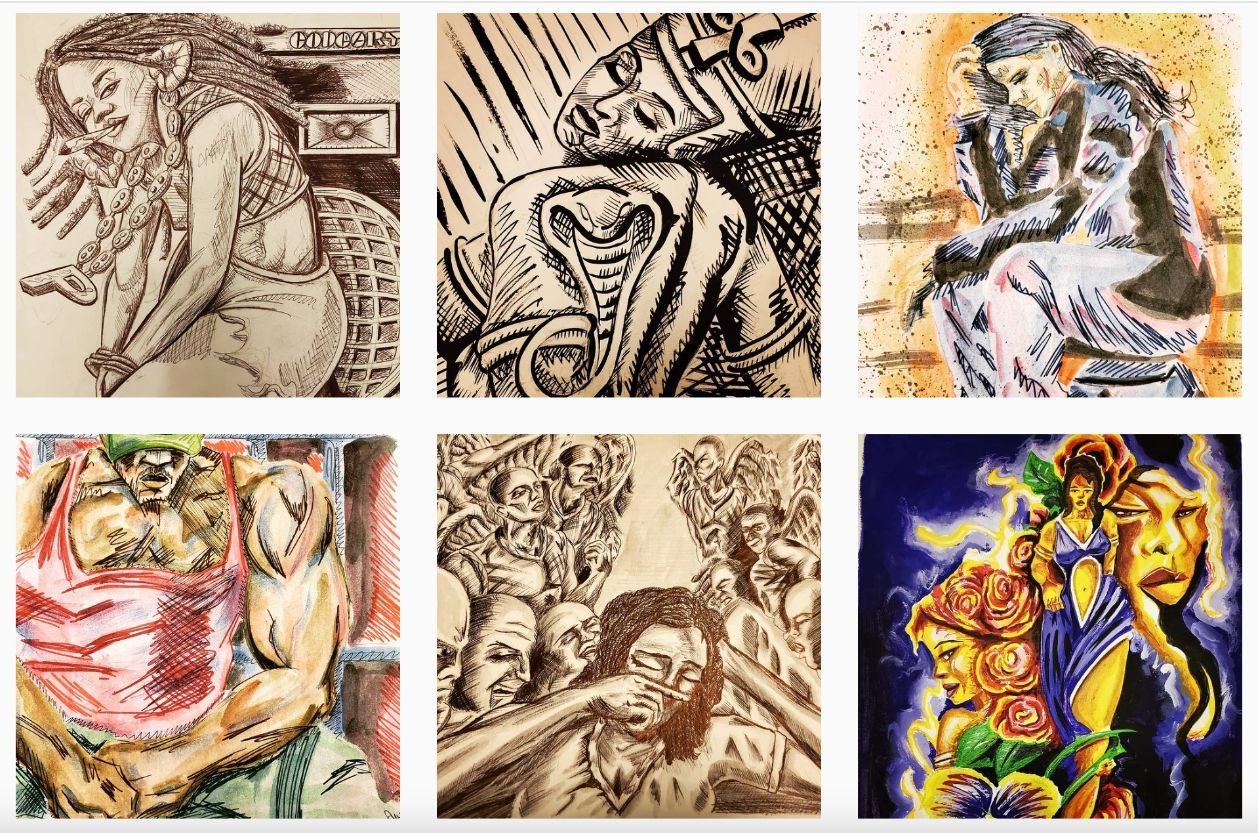

Screenshot from Corey's Instagram account where he shares some of his illustrations.

Almost a year before the pandemic, the bosses said they wanted her to push programs through the General Library. The idea of an art program didn't blow over too well. Fishkill already had RTA. They were the premiere artists who got all the prestige in exchange for silencing the passion of their artistic souls.

The bag lady had a soft spot for hard cases like me on the come up. She leveled us up. From that day forward, we became the Fishkill General Library Illustration Group. No one commissioned us to do anything at first. We just showed up with artwork at organizational events. We won the people over by being persistent. Eventually, they came looking for us to shake the building.

When the pandemic popped off, the administration enacted COVID protocols that didn't permit us to practice our craft collectively. We used to have weekly meetings to collaborate and create. This was also the only time we could gain access to the tools of our trade supplied by the program. Depression began to drip from my brush and my pen paused.

My comrade, Strip Club Sal, slid through and said something slick. "Yo Ceez, you got the spot on smash. Put the dope on the walls mad thick, and don't cut paint. Get 'em hooked on the product. Don't worry about the money, we can slum ‘em with the water colors later. Right now we trying to stop them dead in their tracks when they see the raw. Feel me?"

His words empowered me to reimagine the entire scheme from the love of my people. I got with the crew. Then we went deep into a new type of dark.

Some said we were the special ops of the art world. When the COVID cases went up, we went low tech to teach our community how to protect themselves. We use the cover of sanitizing the common areas and hallways to depict our determination to never stop drawing. Our graffiti had gyrated around COVID guidelines. On the low, between social distance symbols and sanitizing signs some of us signed our greatest pieces.

We forced our way into the fight. We faced our own fears in the eyes of faces we drew half covered by mask, half exposed by terror. It was madness, but we made it work. We did more than mark up face masks, we left the mark of the masses so that they'd never forget.

I'm from the bottom so I did something different. I spit on some scrap paper and sketched the impression of imperfection on purpose. I cried at my own disgust and insanity. I peeped it from a different point of view and titled it, "A Work In Progress.” That's me. That's how we give it up at the bottom — art on demand, by the command of our desire to draw.

Support Corey's work

Read more of Corey’s writing on Medium and check out his visual art on Instagram. He can be contacted directly through JPay. He also asked readers to support, donate, or volunteer with Empowerment Avenue.

Support the art rebellion

Help me reach 500 subscribers. Please forward this newsletter with a friend and ask them to sign up for the art rebellion!

Happy Father’s Day and Happy Juneteenth! To quote a 2020 tweet from journalist Farai Chideya, “take a moment to reflect on what freedom means to you and how you can actively aid the freedom of others.”

See y'all next month.

Our mailing address:

4800 Hollywood Blvd.

Los Angeles, CA 90027

Copyright © 2022 the art rebellion, All rights reserved.