January 2022: Welcome to the art rebellion

I’m so excited to welcome you to the art rebellion

I’m so excited to welcome you to the art rebellion

An introduction

By Makeda Easter

I’m so excited to welcome you to the art rebellion, a new media platform spotlighting artists who are also activists. My name is Makeda, and this project has been in the works for almost two years. It feels amazing to start putting it out into the world.

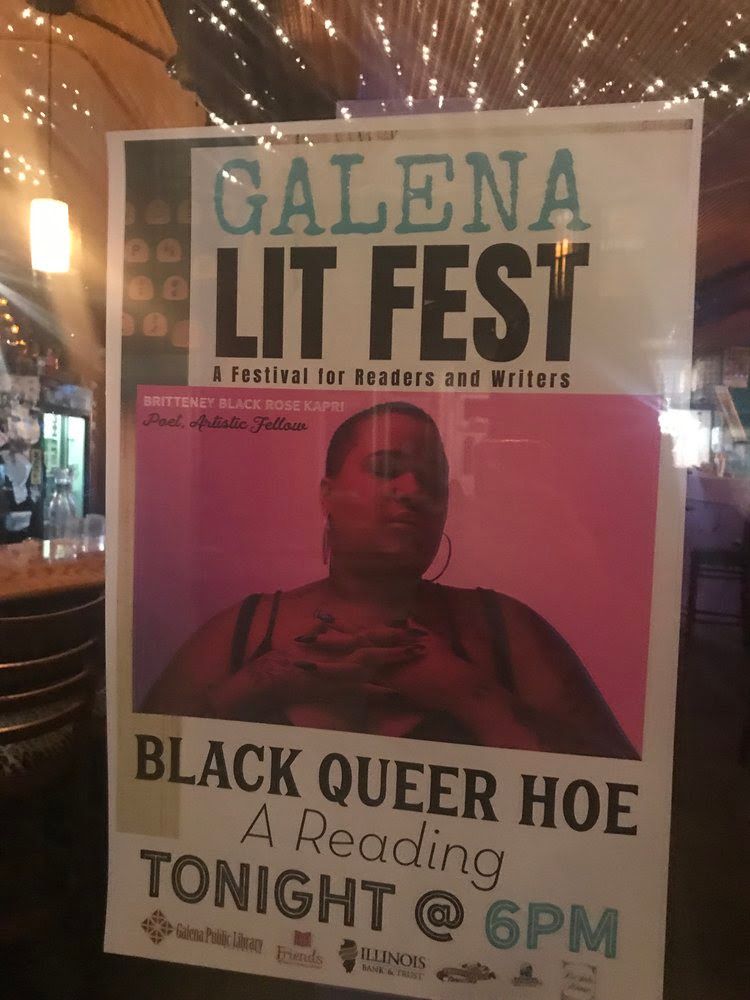

Back in 2019, I was visiting my fiancée’s family in Galena, IL a tiny, quaint, and very white town of about 3,000 people. Wandering through the main street full of gift shops, bars and restaurants, a flyer in a window caught my eye. It was advertising a “Black Queer Hoe” reading by performance artist Britteney Black Rose Kapri. I stopped to take in the flyer, both puzzled and fascinated. If I had encountered the flyer in L.A., where I currently live, I likely would have thought, “oh, that’s cool,” and moved on. An artist sharing work around Black sexual liberation is exciting, but not too out of the ordinary in a city filled with radical performers.

I was in Galena though. At the time, I didn’t realize Britteney was a Chicago-based artist on tour, but back then, I had so many questions: Why perform this progressive work in a rural community? Would she face any resistance while sharing her art? What other boundary-pushing artists are working in small or conservative communities? For the artists working outside of New York and L.A., are there more opportunities to make a tangible impact?

Why aren’t more outlets writing about these artists now?

While I wasn’t able to see Britteney’s performance, the flyer has been seared in my memory. At the time, I covered arts and culture for the Los Angeles Times, and much of my work and the work of the arts team focused on longstanding, incredibly wealthy institutions in the city. Many of the artists I covered were well-established in New York and L.A., with public relations teams helping them to land even more coverage. Even though I tried my best to write stories that appealed to a diverse audience, many of the people reading my stories were white and wealthy.

I’m glad I still have this photo in my camera roll. The flyer that started it all.

I thought about other arts media I consumed. Much of it was also centered on artists working in major cities. In 2020, during the uprisings for Black lives, I thought more deeply about how essential artists are in leading social movements. Even though artists push our society forward, they are neglected — underappreciated and underpaid — and during the pandemic struggling even more to survive.

And so, this idea for the art rebellion emerged.

This platform and monthly newsletter will highlight artist-activists working in communities that have been overlooked in mainstream media. Over time, I’ll develop free, short-form guides on topics that focus on career advancement, rebelling against white supremacist art institutions, and making a living through art. This is a space for people obsessed with art and social justice and marginalized groups who don’t often see themselves reflected in media.

I’m excited that you all are here.

(A side note: some of you might be wondering how you got here. In late 2020, I sent out a survey as I was developing the art rebellion, and some of you expressed interest in getting an update).

Photo of Doris A. Fields from her music video “Disturbing My Peace”

Interview with Doris Fields

For my first interview, I caught up with Doris A. Fields, aka Lady D, a singer, songwriter, actor, and writer, based in Beckley, WV. I met Lady D in early March 2020, when the pandemic was something of a looming question mark for many people. I was in West Virginia reporting an L.A. Times story about the connection between the state’s history of slavery on its salt mines and a collection of documents at Huntington Library in the L.A. area. I reached out to Lady D because I wanted to learn more about her artistic journey as a Black woman in Appalachia.

At Tamarack Marketplace in Beckley, she told me a snippet of her story. Lady D grew up an only child in Charleston, WV. Her father, who was heavily involved in union organizing, worked in the coal mines for 50 years, beginning at just 11 years old. “He was the kid they would send in with the lantern and the canary in the cage to check for methane,” she said.

Lady D began singing in church as a young girl and over the years, the 62-year-old has lived in Biloxi, Japan, Ohio and Atlanta — but she always returned to West Virginia. It’s in her home state where she carved out her own lane, making a name for herself by performing for Theatre West Virginia, forming an R&B, soul, and blues band called Mi$$ION, creating a one-woman stage play based on the life and music of blues legend Bessie Smith, and organizing events like the Simply Jazz and Blues Festival.

Late last year, I reached out again. I wanted to know how she was navigating the pandemic as an artist. As it turns out, she’s thriving. The past two years have been the most lucrative of her artistic career. Like most artists she knew, Lady D turned to Facebook Live to continue performing when the pandemic hit. She also started painting, and was surprised when friends and acquaintances began reaching out to buy her work.

She had been working on a new blues album when the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd forced her to change course and rearrange songs. The album became “Disturbing My Peace,” an expression of her inner turmoil and outrage during that moment of time.

In “Karma Is a Bitch,” she sings: It don’t pay to be a Black or a brown man, cause your life means nothing at all/ Who does it benefit to live in fear and hate or hide behind a wall/ Oh but you know the system is a fraud, but karma is a bitch and she works for God

Her social media became another outlet to voice her rage and frustrations with injustices she saw in her community and across the country. “I don’t feel like a celebrity, even a local celebrity. But people seem to put me on a pedestal in a way. People were waiting to see what I would say about certain things. People were messaging me to talk more about what I had posted,” she said. “Everybody has something that they were placed here to do. Mine was not to march in the street — somebody’s got to do that. And I want to be a supporter of those people who do that. But mine is to write about that and vocalize what they’re doing.”

In 2020, Lady D also began receiving some unexpected opportunities, including a performance at an online Kennedy Center concert and a teaching gig with a university. She was booked and busy.“A lot of white guilt has gotten me a little further along,” she said, laughing. “You get a lot of people looking for things, maybe they weren’t even thinking about booking you, but figured they better try to be a little more diverse in their events.”

There’s only been one gig I actually had to turn down [in 2021] because they didn’t want to pay my price,” she said. “That’s a whole new thing, and it’s late in life but it’s here so I’m just gonna run with it.

She was conditioned to working for scraps. It’s hard being an R&B and blues singer in a state obsessed with country and rock music. She recalled some degrading experiences in the early years after returning to West Virginia — being asked to sing on the spot for a gig at a bar, driving hours to a gig only to receive $50, singing at events where the audience was racist or where she felt like “the help.”

“Living here in West Virginia, I’ve had to perform for people — private parties and things that I would never normally have been invited to that party. And sometimes, you’re performing and you overhear people talking around you who are clearly racist and you still have to smile and do your job there and act like that doesn’t bother you. [2020] just really broke the straw for me as far as being quiet about these things.”

“I don’t want to go back to that at all,” she said. “This past year, I’ve been able to say, ‘well I need $2,000 for this,’ and people say, ‘fine.’ I’m not used to this so I don’t know, I guess there’s been a change in me that maybe other people can see.”

She’s felt a shift in her spirit and attitude during this turbulent time, and has found the type of confidence to live in her truth and reject work that doesn’t serve her. And after a period of growth, Lady D is ready to level up even further.She wants to be in a Broadway show, she wants to tour her music. She’s currently writing a book about Black musicians in West Virginia.

“The whole country thinks West Virginia is those people they see on the news. And I just want there to be an acknowledgment of Black people, who we are, who we were, what we did, especially in the context of music.”

Lady D began painting during the pandemic as another creative outlet.

Support Lady D

Stream “Disturbing My Peace” on Spotify, Apple Music, and TIDAL. Follow Lady D on Facebook or Instagram.

I'd love to hear from you

What did you think about the interview? Do you know of any radical grassroots artists that deserve recognition? Have another idea to share? Send me a note at makeda@theartrebellion.net.Thanks for following along and I’ll be back in your inbox next month!

Our mailing address:

4800 Hollywood Blvd.

Los Angeles, CA 90027

Copyright © 2022 the art rebellion, All rights reserved.