Quilting for Abolition: Interview with Rachel Wallis

The radical history of quilting informs her work.

The radical history of quilting informs her work.

Quilting and Abolition: An Interview with Rachel Wallis

What does it mean to be a radical quilter? This month's interview features a community-taught artist working toward social justice.

By Makeda Easter

The child of organizers, some of Rachel Wallis’ early childhood memories include being “bored and miserable on marches.” She followed her radical family tradition, all while dreaming of being an artist growing up. At Wesleyan University, Wallis got involved in international solidarity and immigrant rights work. After college, she worked in nonprofit fundraising for progressive organizations. A serious bike crash at 30 is how Wallis found her way back to art.

For months, she couldn’t walk, which “meant that in the short term I definitely couldn’t organize the way I had before,” she says. “I couldn’t rock three hour meetings, four nights a week anymore. And I couldn’t do marches. It was really a huge loss for me. I didn’t know how to be in the world or in the community without these things anymore.”

The process of making became a way to heal. After joining a mostly Latina stitch and bitch group in Chicago, she began working on a 2012 textile-based Day of the Dead exhibit at the National Museum of Mexican Art. The group made an embroidered quilt, each square dedicated to women in their lives who had passed away. “Just hearing everybody’s stories and feeling how powerful the making and talking and processing and thinking about things visually, as well as emotionally, felt really magical to me.”

“It felt like a really physically and emotionally sustainable way that I could be engaged in movements and doing organizing that felt meaningful. And be disabled.”

In the years since, Wallis has found creative ways to merge her dedication to social justice with her art. In 2015, she began a three-year project, “Gone But Not Forgotten.” Collaborating with anti-police violence group, We Charge Genocide, she organized a series of quilting circles memorializing nearly 150 people killed by the Chicago Police Department or in police custody since 2006. While reading victims’ stories out loud, the group collectively stitched a six-panel, 40-foot long quilt including victims’ names, ages, and dates of death.

Video from Gone But Not Forgotten project

In 2018, Wallis taught quilting to groups of women in the Cook County Detention Center and other prisons throughout Illinois. The project involved classes where mothers shared stories about family relationships and designed an original quilt for someone in their family. Then, volunteers on the outside sewed each woman a quilt based on their designs and mailed them to the recipient of their choice.

Wallis draws on the radical history of quilting in her practice.

“You can see back to the early abolitionist movement, quilts were not only used as fundraisers to fund the anti-slavery organizing, but quilters would include anti-slavery illustrations or poetry or themes in the quilts themselves to try and generate sympathy and understanding for their cause,” she says.

Now 41, Wallis lives in Columbus, Ohio and works at Sew to Speak, a progressive textile fabric shop where she teaches quilting, block printing, sewing, and embroidery. As a white woman, Wallis says quilting can be a Trojan horse — a way to inject progressive ideas into unexpected spaces. “It’s an interesting way for me to organize around other white women — creating these radical spaces where I can talk to white women about white supremacy and racial justice issues in a way that hopefully is both intimate and powerful.”

Inspired by her past work, she is organizing a quilting program at the women’s prison near Columbus. Wallis will meet with a small group of women each week, helping them develop basic sewing and quilting skills, so they can make quilts to either donate or sell. Participants will have autonomy over the direction of the project, and she eventually hopes to develop a textile art exhibit with the group.

Inheritance Quilting Circle at Pozen Center for Human Rights 2018

How can someone practice abolition while working within the prison system?

“It’s really hard,” she says. “I constantly have a voice in my head that’s like, ‘how can I talk about my work and my politics in a way that’s honest, but doesn’t close off my ability to access teaching in prisons?’”

Being an abolitionist means constantly working toward a world without police and prisons. “Thinking about my political actions and the way I live my life — is this giving power, control, access to police and prisons, or is it building avenues outside and beyond them? But that’s a very long, slow road.”

“In the meantime, I also just want to do the things that I could do to help people survive on the inside.”

In October 2020, she was named the first artist in residence at Project NIA, an organization working to end youth incarceration through community-based alternatives to the criminal legal process. The residency provided Wallis with $15,000 and a year to create abolitionist art. She had already worked with Project NIA founder and community organizer Mariame Kaba on the “Gone but Not Forgotten” project. Kaba was researching the 1947 massacre of 8 Black men imprisoned at Anguilla Prison Camp in Georgia. The men were murdered by warden and guards after refusing orders to dig a ditch barefoot in waters filled with venomous snakes.

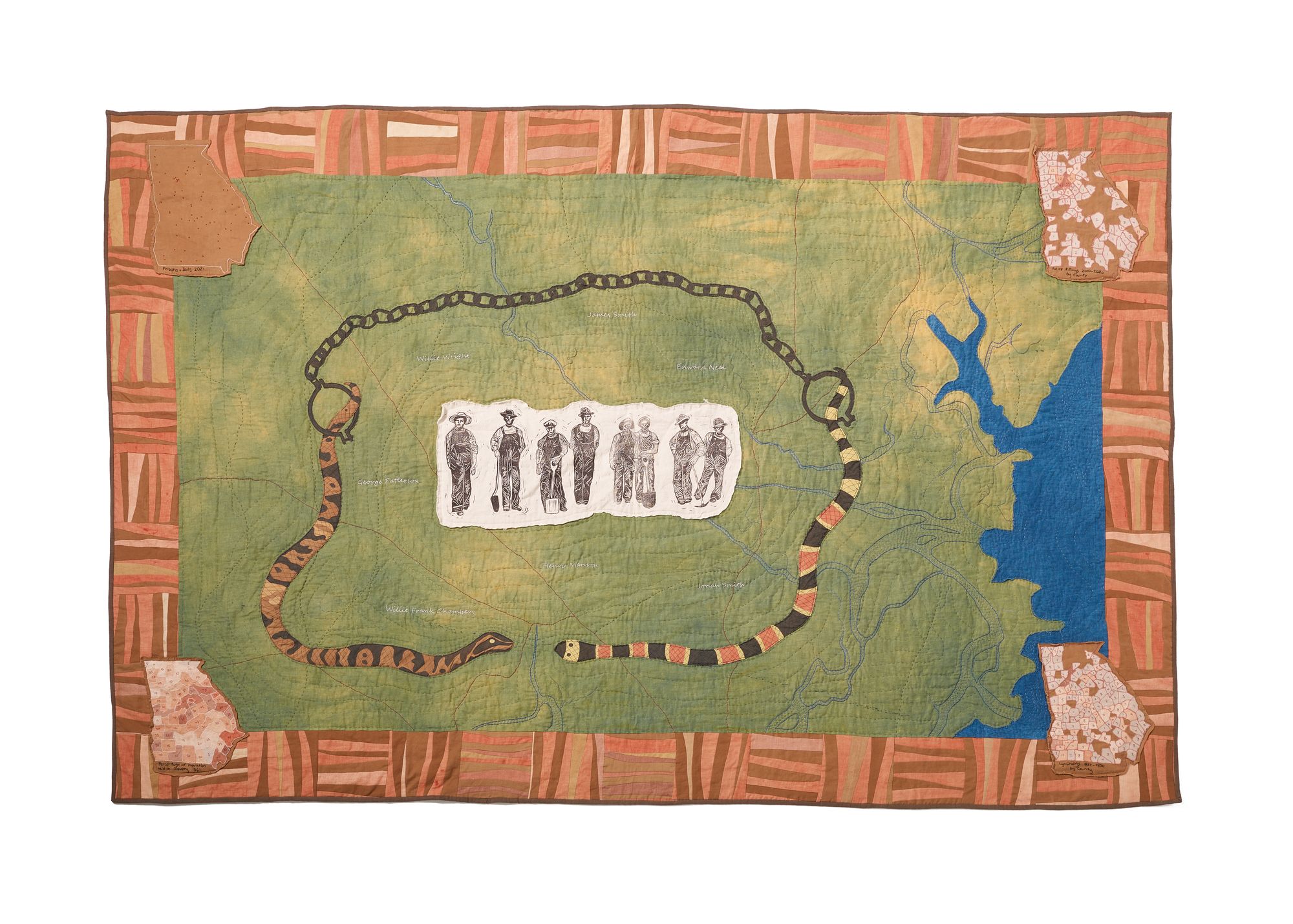

Wallis created the Anguilla Massacre Quilt during a year-long artist residency with Project NIA. Bryce Laughlin Photography

Kaba wanted art to accompany her work as another educational tool. “She gave me this huge trove of historical research that she had amassed for her own writing and was like do whatever you want,” Wallis says.

She began by learning about natural dyes as a way to acknowledge the people who worked the land. “So much of the South was transformed by prison labor,” Wallis says. “I was talking to an archivist in Georgia about which of the major roads in Georgia were probably built by prison labor, and she was like, ‘all of them.’”

Made out of a rough-spun cotton and hemp fabric, Wallis then dyed the quilt with plants that could grow in Georgia.

She describes the quilt as “maps, within maps, within maps.”

There were no photos of the men who were killed, so the front of the quilt is based on a photo of a chain gang (groups of prisoners forced to labor while chained together) from around the same time period. She couldn’t find an address of where the prison camp was located, but knew the general location.

“Trying to find some scrap of these men’s history outside of their imprisonment and their death, there really wasn’t anything that I was able to find. So instead, I looked at what is there and a lot of times for me, that’s maps. So looking at maps of enslavement in Georgia, looking at maps of lynchings, looking at maps of police killings, and where prisons and police stations and jails are now. Pulling these all together to try and tell a tale of the ways that the system of exploitation that was slavery moved seamlessly into the system of exploitation that is policing and incarceration.”

Wallis also worked with Kaba to weave in references to the story of resistance amid tragedy.

The killings were described by the New York Times as the result of a failed escape attempt. “Nothing more would have come out of it were it not for a letter one of the survivors wrote to the local NAACP branch, who were then able to organize and demand justice. There were several trials. No one was ever convicted of the massacre, but everything that we know about it, we know because of the bravery of the survivor and the work that the NAACP did locally and nationally.”

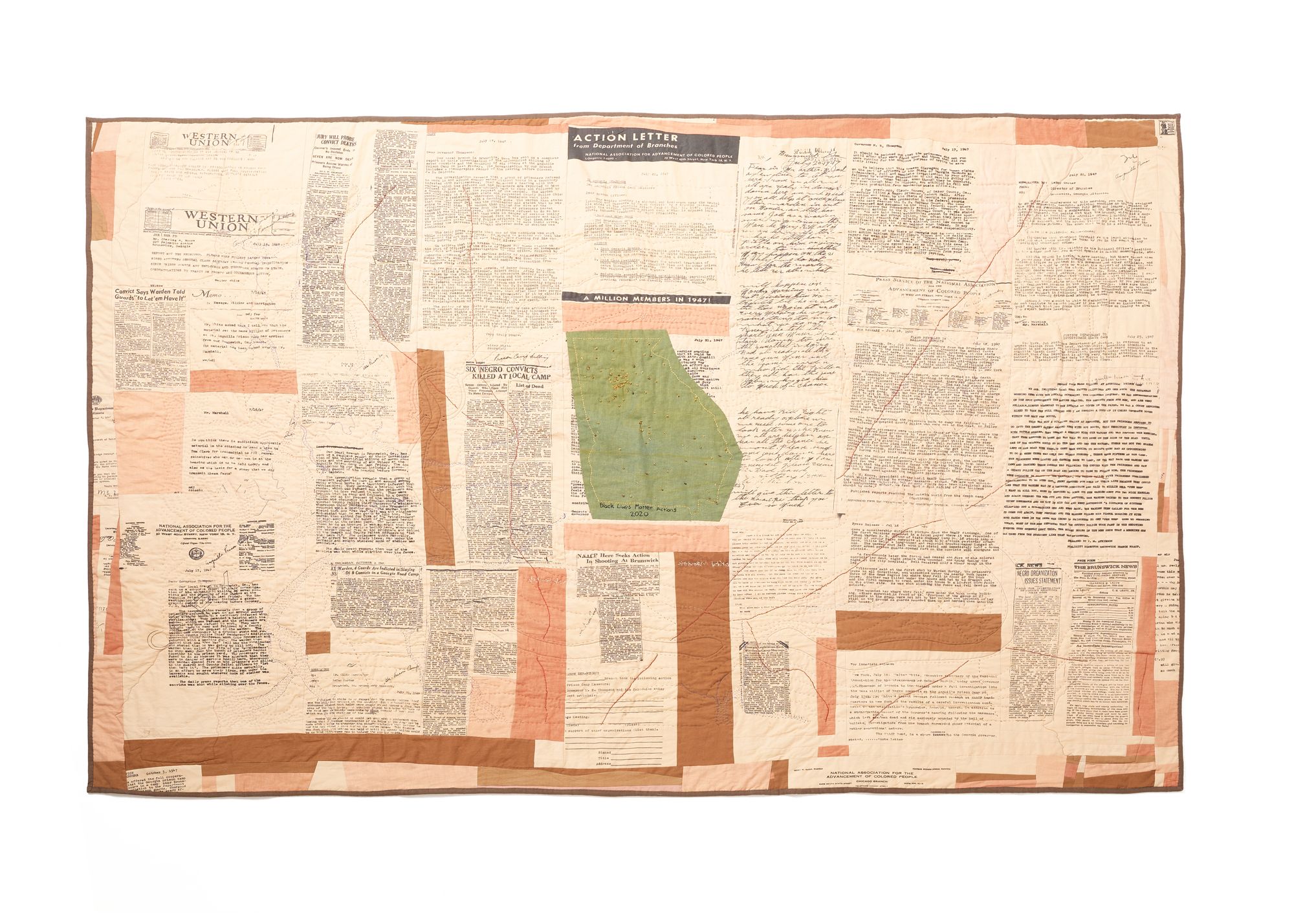

Back of the Anguilla Prison Massacre Quilt. Bryce Laughlin Photography

On the back of the quilt, Wallis digitally printed the primary source documents from the NAACP archives, and a map of Black Lives Matter protests from 2020 in Georgia, “so that it can be reflections of the history of violence and subjugation, but also the history of resistance and pushing back.”

Wallis finished the 7.5 feet by 5 feet Anguilla Prison Massacre Quilt in 2021 and plans to exhibit the work in Chicago this summer.

She emphasized the quilt would not have been possible without her collaborators, which speaks to the evolution of how she has come to describe her artistry.

For a long time, Wallis referred to herself as a self-taught artist, because she didn’t go to art school. “The longer I work, the more I realize that most people aren’t self-taught. Especially when it comes to textiles and when it comes to quilting, so much knowledge has been passed on from generation to generation, within families, within churches, within communities. And that has formed so much of what I know and understand about quilts.”

Now, she describes herself as a community-taught artist. “It’s just always trying to point back to the fact that everything I do is made better by the people in my life who have contributed, and the people who came before me who I didn’t know contributed to that.”

Interview Bonus

As I’ve continued reporting for this project, one of the questions I often ponder is what exactly is art activism? Is raising awareness enough? What does it mean for an artist to also be classified as an activist? Does tangible change have to come from art for it to be considered activism?

I asked Rachel some form of this sprawling question and wanted to share her full response:

When I was younger, I was a lot more sure about that than I am now. After I started quilting, I went back and I got a master's in socially engaged art at Moore College of Art in Philadelphia. And while I was in that program, and I think for a little while afterwards, I was probably abrasive about, I'm not interested in raising awareness or starting conversations. I think if your art is not directly tied to ongoing activism by people who are most impacted, it's useless. And I still think that is a really good question to ask yourself as an artist. What is this changing? Who is this helping? Who is materially benefiting from this? Am I the only one getting paid in this room or getting attention or getting prestige out of this?

I still want to and try to collaborate with grassroots groups, both in my big “A” art projects, but I'm usually making and selling things as fundraisers for groups that I care about, because I have much more time and fabric than I have money. As I've gotten older and less sure of myself and my place in the world, I've made more space for art as a way of learning and as a way of understanding. So doing projects that are really about researching and about learning and maybe about sharing that learning with other people. But that might not have an action component at the end of it.

I just finished a residency this fall with my amazing friend and collaborator Sangi Ravichandran at the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester, New Hampshire, where we spent a month dyeing and weaving and talking about the history of colonialism and labor and textiles and reading and discussing, and it was incredibly powerful and broadening — maybe just for the two of us. But possibly for other people who are in conversation with us. But I don't think any sort of profound social change is coming out of that experience. And also, I think it was worthwhile and I feel really lucky that I got to be a part of it. Maybe it's okay for art to be a conversation and a learning, as well as a hammer.

Support Rachel Wallis

Follow Rachel's work on Instagram. And check out “Stitch by Stitch: Conversations on Quilting, ‘Healing' and Abolition,” a conference she is co-organizing this July in Chicago. From the event’s about page: “Stitch x Stitch is a convening situated within a long historical conversation between quilting and social justice…We seek to explore how quilting can serve as an embodied, liberatory practice and the role it plays in facilitating new forms of liberation. We also wish to interrogate definitions of 'healing,' both productive and problematic, and its intersections with quilting and work of the hand.”

More personal news

I was recently selected to join the 2022-2023 cohort of Knight Wallace fellows at the University of Michigan. Read the announcement here. This means I will be able to focus on the art rebellion by taking classes, reporting more stories, and connecting with artist-activists in the Midwest. This is such a gift and privilege, and I’m looking forward to growing this platform. Please send me all the Ann Arbor/ Detroit recommendations!

Have thoughts on this month’s newsletter? What types of stories would you like to see in the future? Hit reply to this email and let me know your thoughts. And please consider forwarding to a friend!

Our mailing address:

4800 Hollywood Blvd.

Los Angeles, CA 90027

Copyright © 2022 the art rebellion, All rights reserved.